We also have Rec Letter Guides for:

Written by Alexis Allison, College Essay Guy Team

When I was a high school English teacher, my greatest nightmare was that my students would form a mob around me and overpower me (thank goodness it only happened once).

Even so, the same overwhelming feeling of angst bore down upon me every year around application season. As your list of recommendation letters for students continues to grow, maybe you can understand.

But fear no more! We’ll show you why writing strong recommendation letters for your students can be one more way to serve them in their future academics. While we’re at it, we’ll also walk you through how letters of recommendation for teachers differ from the counselor letter; then, we’ll offer you two different schools of thought on how to write recommendation letters for students.

Both approaches work well, so we’ll show you how each is done—with examples for your reading pleasure.

In the spirit of this topic, we’ve gathered advice from a number of experts, including:

Chris Reeves, school counselor and member of the NACAC board of directors

Trevor Rusert, director of college counseling at Chadwick International in South Korea

Michelle Rasich, director of college counseling at Rowland Hall

Kati Sweaney, senior assistant dean of admission at Reed College

Sara Urquidez, executive director of Academic Success Program, a nonprofit that promotes a college-going culture in Dallas/Fort Worth high schools

Martin Walsh, school counselor and former assistant dean of admission at Stanford

Michelle McAnaney, educational consultant and founder of The College Spy

And I’m Alexis, a high school English teacher-turned college counselor-turned journalist. Ethan (the College Essay Guy) and I serve as your synthesizers and storytellers in this guide, which we’ve chunked into a few parts:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(click to scroll)- Why Writing a Recommendation Letter is Important

- The DOs and DON’Ts of Writing a Recommendation Letter for Students

- The Traditional Approach

- Example: The Student Who’s Faced Adversity

- Example: The High-Achieving Student

- Example: The Introverted Student

- Example: The Middle-of-the-Pack Student

- Example: The Outlier Student

- The Organized Narrative Approach

Why Writing a Teacher Recommendation Letter is Important

What’s the point?

Well, most of us became teachers to actually help students (although grading is a crackerjack good time, too). We know these letters take time and energy, and can sometimes feel thankless. But a well-crafted teacher recommendation letter can truly make a difference for your student. And for students who come from low-income homes or have especially tough circumstances, it’s the opportunity to advocate on their behalf.

Recommendation letters have some serious clout in the admissions process. Some colleges consider letters of recommendation pretty darn important—above class rank, extracurricular activities and, at least when it comes to the counselor recommendation, demonstrated interest (dun dun dun!).

Check out the results of the 2023 NACAC “State of College Admission” survey:

Our buddy Chris Reeves, a member of NACAC’s board of directors, has another way to read this table: “If you consider ‘considerable importance’ AND ‘moderate importance,’ the teacher letter is also more important than demonstrated interest.”

Basically, if it comes down to your student and another candidate—all else being equal—your recommendation letter can get your student in or keep them out.

And, according to a presentation co-led by our friend Sara Urquidez at a 2017 AP conference, rec letters can also help decide who gets scholarships and who gets into honors programs. All told, they’re kind of a big deal.

As teachers, you provide a key source of information about something that test scores and transcripts can’t—your student’s role in the classroom. If you’ve ever seen or written a counselor recommendation letter, you’ll notice some similarities.

But know this: While the format for these two letters of recommendation may be very much the same, the content should differ.

Here’s how:

Teachers, according to Martin Walsh (former assistant dean of admission at Stanford) and a presentation co-led by Sara Urquidez (executive director of Academic Success Program), your recommendation letter should describe:

the impact this student has on the classroom

the “mind” of the student

the student’s personality, work ethic and social conduct

On the other hand, a counselor’s letter should describe:

the student’s abilities in context, over time—how do they fit within the school’s overall demographics, curriculum, test scores?

special circumstances beyond the classroom that impact the student

But does anyone actually read my recommendation letter? (Or am I just shouting into the dark, dark void?)

Yes! (To the first question) Your letter will be read and rated, sometimes by multiple admissions reps at each school.

What do I mean rated?

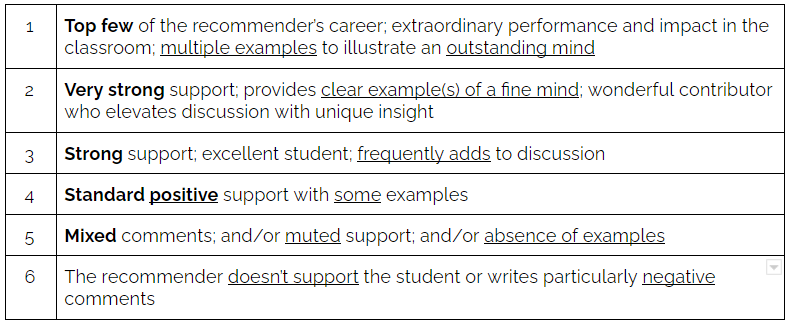

Well, your letter may get a sort of grade that will (hopefully) bump your student up in points. Here’s a rubric and some instructions admissions representatives used to follow to assess recommendation letters for students (courtesy of Martin Walsh).

Where did Martin work again? Stanford.

(PSA: The rubric is about 15 years old, but Martin thinks it can still shed some insight on the evaluation process.)

“In general, our candidates receive good, solid support. For many of our private school applicants, hyperbole can be more the rule than the exception; guard against over-rating such comments. Note if there is consistency among the recommenders. Do they corroborate or contradict one another?

Watch out for the “halo effect,” where a parent or other relative of the applicant may be on staff at the same or another school or be a VIP in that community. Watch for recommenders who use the same basic text for every student for whom they write, or who write inappropriate comments. Do not penalize a student whose recommender’s writing style is not strong. Don’t penalize a student for what is not said. Some teachers/counselors are better recommendation writers than others.

The rating should reflect both the check marks and the prose, and also should reflect the overall enthusiasm the recommender has for the candidate.”

Now that you know the key differences in content, and that your letters WILL be read, it’s time to dig into the nitty gritty.

The DOs and DON’Ts of Writing a Teacher Recommendation Letter for Students

We asked Kati Sweaney, senior assistant dean of admission at Reed College (a woman who’s read thousands of rec letters, phew!), to give us some know-how. Here’s her top list of DOs and DON’Ts for teachers when it comes to the recommendation letter:

DO:

Tell me a story. Kati says, “It's the character stuff that I really need to hear from you … I need to know what kind of community member I'm getting—you're my best (sometimes only) source.”

Pick specific descriptors and back them up with evidence; avoid cliches like “hard-working,” “passionate,” and “team-player.”

Show me good student work. Copy and paste an especially well-writ paragraph from your student’s best essay, or a screenshot of clean coding they did in class. Here’s Kati: “Be brief in how you set it up, but it's cool to let the student speak for themselves.”

Ask permission if you're going to reveal something private about the student (they have a learning disability, their mother has cancer, they struggle with depression).

DON’T:

Write your autobio. The letter’s about the student, not you.

Repeat a student’s resume. Admissions counselors get a copy of that, too. Kati says, “I know this comes from a desire to portray the student as well-rounded and also to pad out what you're worried will be a short letter, but trust me: Two paragraphs actually specific to the student are so much better than a page of puff.”

Address letters to a specific school. It’s awkward if Stanford reps are reading your letter and it talks about how much the student loves USC.

Recycle letters—even those you wrote in previous years. Here’s Kati: “I read high schools in groups—so, if I get five applications from Montgomery High, I read all five of them right in a row. It does your students zero favors if I see you are not writing them individual letters. And next year, I will also be the person who reads letters from Montgomery High.”

So, how do we go about writing them?

As we said in the beginning, we’re going to walk you through two different approaches. The first we call the “traditional” approach.

If you’ve ever written or received a recommendation letter in your life, it’s probably looked like this one. The second is a newer, more innovative approach; its creators call it the “organized narrative.”

Intrigued? Read on.

The Traditional Approach to Writing a Recommendation Letter for a Student

This is your typical letter of rec. It looks, well, like a letter. Long paragraphs. Transition words and phrases. Indentations. That sort of thing. It’s a tried and true method.

So you’ve probably seen these. But how do you actually write one well?

Our friend Sara Urquidez, executive director of Academic Success Program, has written a detailed set of instructions for these rec letters—broken into three parts: Introduction, Body, and Conclusion.

(Remember, this is one way to do it. It’s great! And we’ll also show you some examples. But, if you want to jump ahead to the newer approach—the Organized Narrative—be our guest.)

To Whom It May Concern:

Introduction

Hook: Start with a simile/metaphor, an absolute statement, a surprising fact, a colorful characterization.

The first line should provide the full name of the person that you are recommending.

Make the letter general so that it can be recycled for scholarships (i.e. do not put “the student would be great at your campus” because it might be used for a scholarship).

State how long you have known the student and in what context.

Body

Discuss the student’s work in your classroom.

Is it timely, organized, creative, thorough, neat, insightful, unusual?

Describe how the student interacts with peers and adults/learning environment.

Are they liked? Do they chose to associate with good people? Do they have good people skills?

Do people, especially adults, trust them?

Are they kind/sympathetic/considerate?

Leadership: Do they lead by example or do they take charge? Do they work well in small groups? Participate actively and/or respectfully in whole class discussion? Work well independently? Understand how to break down complex tasks? Suggest modifications to assignments that make them more meaningful? Support weaker students?

Describe the things that you will remember about the student.

Go beyond diligence and intelligence: Talk about humor, courage, kindness, patience, enthusiasm, curiosity, flexibility, aesthetics, independence, courtesy, stubbornness, creativity, etc.

ALWAYS talk about work ethic if you can.

ALWAYS talk about integrity, at least in passing, if you can.

Quirks are GOOD. Individuality is GOOD. It’s okay to talk about a student being obsessively into anime, or John Green novels, or Wikipedia. Talk about how they always doodle, always carry a book, play fantasy cricket. It’s good to talk about how a student deals with being different—because of their race, their sexual orientation, their religion, their disability. Do not shy away from these things.

Talk about why you will MISS THEM.

Describe how the student reacts to setbacks/challenges/feedback.

Detail any academic obstacles overcome, even if it is partially embarrassing, negative or controversial.

Do they take criticism well? Do they react well to a lower than expected grade? Did they ever deal with a crisis or emergency well?

How do they handle academic challenges? Come to tutoring? Request extra work? If a particular area showed marked improvement over the year, explain what the student did to make it happen.

Do they ask for help when needed? Do they teach themselves? Do they monitor their own learning? Do they apply feedback/learn from mistakes?

Provide evidence and examples of personal qualities.

Physical descriptions can be very useful here. If this feels strange to you, Sara notes that it’s a way to make students (who may look like everyone else on paper) memorable: “When you can imagine the student who wears a cape and a fedora to school, it makes the 36 and the 4.0 a lot more interesting … we found this was a way to breathe life into applications that might have gotten lost in the shuffle by making the students human to the reader.”

Think about anecdotes the student has told about their lives, ways they describe themselves, about papers/projects completed, about tutoring patterns, about the time they did something dramatic in class.

Reference significant projects or academic work, especially those that set a new bar for the class.

Identify the student’s engagement, level of intellectual vitality, and learning style in your class.

If you teach English/history: You MUST address how well they read. Complex things? Archaic things? Do they see nuance and tone and subtext? You MUST also address how well they write. Is it organized? Creative? Logical? Intuitive? Functional? Do they have a strong voice? Can they be funny? Formal?.

If you teach math/science: You MUST address how the student analyzes information/handles abstraction. Are they good at categorizing? At visualizing? At explaining? How do they tackle a new topic or strange problem? Think about what their homework/tests LOOK LIKE when you grade them. What does that tell you about how they think?

Include only first-hard knowledge of extracurricular involvement. No lists, please.

Extracurriculars only matter because they show something about the student—a passion, a skill, a talent. The extracurricular is going away—what will they take with them? What will they bring to campus?

Extracurricular achievements are best used as examples to demonstrate earlier points, not as a goal/paragraph in themselves.

If you are a sponsor, think beyond the activity itself—think about reacting to setbacks, supporting team members, organizing events, making suggestions that changed how the team/group did things, setting an example, and growth over time.

Conclusion

Begin with an unequivocal statement of recommendation. “[Full Name] carries my strongest recommendation.”

State what the student will bring to an institution (NOT why the student deserves acceptance).

Summarize the student’s qualities and accomplishments that you wish to emphasize.

End with an emotional comment—that you will miss them, that you have learned from them, that you are sorry to see them go, that they are your favorite, etc.

Final tips from Sara

Have someone edit/review your letter of recommendation. Your school’s college counselor is a great place to start. From Sara: “You'd be surprised how many people don't actually know what to write/not write in these letters, particularly in schools without a strong culture of recommendation writing … The back reading of recommendation letters by other faculty members allows us to prevent saying the same things over and over and cover more information as required.”

Let the student know if you have chosen to include any negative or sensitive information so that they remember to address it in their application.

Sign the letter—and put it on letterhead. (If you don’t know how to sign something digitally and don’t want to go through the whole print-sign-scan thing, we found this 3-minute guide easy-peasy to follow.)

Avoid using ambiguous language and hyperbolic clichés. (All praise should be supported with specific examples.)

Ultimately, be specific and detailed. It should be clear that you know and like this student.

What do these letters actually look like?

Sara has gathered a slate of strong teacher rec examples that work for different kinds of students. We’ve included them below:

Example Recommendation Letter - The Traditional Approach:

The Student Who’s Faced Adversity

To whom it may concern:

Jordan has a lot on her mind and more on her plate. When I met her, she didn’t: she was 14, a freshman in my English class, and absolutely irrepressible. She was game for anything: she made friends with everyone, she joined clubs, and started one when she saw a need. She aced every assignment and always turned in homework that showed careful, thoughtful work. She found a boyfriend, and then found out she was better off without him. She was a firecracker, and clearly among the strongest in her class.

It was clear, then, why she was good with chaos: she lived in a tiny little house with her parents and four sisters, and when a baby brother (finally) appeared during her freshman year, she rolled with that, too: my own son is just a year or so older, and she and I would commiserate about teething and late nights and diapers. From those conversations, I realized that Jordan has the gift and burden of being a practical, sympathetic person—sympathetic enough to be driven to help those in need, and practical enough to see what can be done. So when her mom struggled with a house full of babies and a job, it was always Jordan who put down her homework to go get dinner started or to wipe a snotty nose or to fold a load of laundry. The older girls had their sights on the big world and the younger ones were too little to help—it tended to fall on her.

It was clearly a house with a lot of love and not quite enough resources, and while she had more responsibilities than I wished, I mostly admired how well she handled it.

All that changed spring of her sophomore year when her father died. Being a teacher means watching this happen once every few years. The emotional impact is, of course, brutal, but usually it’s relatively simple: the issue is grief, and time does help. But they have six children in the house, 3 not yet in school, and that’s not a simple problem. It’s a world of responsibility and expense, and it’s not something that time can soothe. I cried when I realized she was working part time, because I know how hard she works at school, and I could imagine the grind of her life each day—from the minute she wakes up until she goes to bed, there is an endless need for a pair of hands at home, and then she goes to school to face a brutal academic schedule. Adding a shift at a fast food restaurant before heading home to juggle toddlers and preschoolers and to somehow get her homework done seemed beyond all reason—but the reason was the simple economic need to avoid being a burden on the family, and to help out with some other expenses. I hugged her when she managed to save up enough to quit during AP exams season. I felt like a weight lifted off me—even the sympathy weight was rough —what was the real one like? Of course, she went right back to work when school let out, and when she went back and asked for her job back, they promoted her to shift manager. She spent the summer running a crew of adult full-time fast food workers, and she saved enough to be able to quit for the school year.

I could not do what Jordan does. But she does it. Every damn day. I don’t know that it ever occurs to her that she could let anything go—she passed most of her sophomore AP exams a month after burying her dad, and had an even stronger performance her junior year despite having no time to even think. She never misses an assignment, and I wish they looked more rushed, because I’d feel less guilty about assigning them. Her grades have stayed good—not as good as they would have been, I think, but good—and she’s continued to take the most challenging course load we offer, including the marathon AP Physics/AP Chemistry course we call SuperLab. She’s heavily involved with YWISE, a STEM research program through the University of Texas at Dallas. More tellingly, she’s maintained a social life—she keeps up with her friends, worries about their problems, gossips about boys, and never, ever complains. She still makes it to meetings of the Girl Club she helped found, to dances and to socials. She still indulges in blue or pink hair dye when she can. She’s still a vital part of our community.

But she always looks tired to me, and a little underfed, and it breaks my heart every day.

Jordan is my favorite in that group—she was extraordinary before, and the tragedy of her sophomore year has tempered her into steel. I want, so desperately, for her to have a chance to go away, to apply all that strength and creativity and initiative to changing the world instead of to serving customers and wiping snotty noses. Jordan will be fine, regardless—she’s proved that these last two years. But we as a society need the kind of person she will grow into if placed into an environment that will point her talents towards targets worthy of them.

She carries my absolute strongest recommendation. I am sure there is some concern that she might have family obligations that will keep her from being able to accept a place in a residential program, but I’ve discussed logistics with her and her mother and I am confident that the family is prepared to live without her in the immediate household. I do expect she will have to work in the summers. If you have any other questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Sincerely,

Amanda Ashmead, Humanities Chair

Example Recommendation Letter - The Traditional Approach:

The High-Achieving Student

To whom it may concern:

Taylor managed to find the one school in America where he’d be the odd man out, and he was as good for us as we were for him. He bridges some very different worlds found in highly selective institutions, and I think he’d be a fabulous resource for any such community.

On one hand, Taylor is brilliant: I’ve been in advanced academics and working with extraordinarily talented students for 15 years, and Taylor is, without a doubt, among the strongest students I’ve ever worked with. His faculty for language, in particular, is extraor dinary: he’s one of those analytical/verbal people—he thinks like a philosopher. He can read anything, however archaic or abstract, and never misses nuance or tone. He enjoys cleverness with language—not the easy cleverness of puns but the intricate interplay of sound and meaning that make a sentence or a phase perfect. He writes flawlessly—his natural voice is straightforward and organized and efficient. His scores reveal a similar aptitude for math and science, though I really think even there he’s a word guy—his thinking, his understanding, is verbal in nature. His work ethic is beyond reproach: every assignment done flawlessly, tests studied for, cello practiced, community involvement accomplished. He makes busy look easy.

On the other hand, Taylor is defined by his Evangelical Protestant faith, and he very much belongs to a suburban, affluent Evangelical community. I’m talking church Sunday morning and Wednesday night, Young Life and Fellowship of Christian Athletes. This is a pretty common community in America, but it’s not common at this school, for a variety of reasons: our student body is poor, urban, and minority. We are a STEM magnet with a decidedly secular feel. What with one thing or another, we have more openly gay atheist boys than evangelical Christians at this school, and more kids would admit to being undocumented than being pro-life. When 14-year old Taylor got here, straight from a little parochial white-flight school in the suburbs, it must have felt like he’d arrived in Gomorrah, but with a Freshman Calculus class. But instead of running for it (which I think he seriously considered), Taylor adapted—and the way he adapted is a testimony to his character and the key to why he will be such an important asset in an academic community.

For one thing, Taylor always brings his full intelligence and analytical ability to bear on his faith. There are strains of Evangelical Protestantism that discourage active and sincere questioning, but that is not Taylor’s way. He questions everything, and he always embraces nuance and tone. So when he was suddenly immersed in an environment that challenged rather than reinforced his faith, he didn’t feel threatened—rather, he appreciated the chance to really explore his own beliefs in a new context. Furthermore, his analytical nature means he is able to compartmentalize and to appreciate people that are truly different than he is. I, myself, could not be more different than Taylor in this way—I pretty clearly lean far left, and I know I’ve used cuss words in front of him he probably never even heard before—but we’ve always had a relationship defined by mutual respect and an honest willingness to learn from each other.

Second, he’s a really nice young man who makes friends readily. I’ve watched him develop deep friendships with students so very different from him—racially and socioeconomically, of course, but also ideologically. He has really high and specific ethical standards for himself, but he doesn’t worry about other people. He’s used these last four years to learn about worlds he didn’t know existed, and it’s made him humble and thoughtful. We’ve had other, similar students in his position that didn’t react as gracefully: suddenly being the minority is jarring, and some students react with resentment. Taylor, though, understands his own situation is a shadow of what many of his classmates face in other contexts, and rather than become bitter, he’s become sympathetic and wise.

In many ways, college is traditionally the place where students like Taylor have the opportunity to learn what Taylor already knows—how to get along and work with people that are different than themselves. Taylor will be a catalyst for that process: he can move comfortably in literally any company, and he can translate between very different people—and teach them to connect to each other. If I were putting together a group of students for a long term research program and I was worried about group cohesion, Taylor is the person I’d select because he would be the model and the architect for mutual respect and cooperation. Also, he could write the paper.

Taylor thinks he’s going to be an engineer. No one here believes him. He’ll get the engineering degree, but it’s clear to us he’ll end up doing something larger than that: his skill set is too large, his interests and passions too broad, his gifts for working with people too profound. I don’t know exactly what he will do—entrepreneur, author, large-scale project manager?---but it will be remarkable. He’ll be a huge asset to your community from day one, and be a credit to the institution for decades after. He carries my very strongest recommendation. If you have any questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Sincerely,

Amanda Ashmead, Humanities Chair

Example Recommendation Letter - The Traditional Approach:

The Introverted Student

To whom it may concern:

Somewhere on your campus you have a professor who will be really glad you accepted Taylor. He’s that kind of student—the sort to be liked and respected by his classmates, but really appreciated by the professors who will see what is so clear to any adult paying attention—Taylor has the soul of an academic. Right now, he thinks he’s getting a degree in a STEM field and then a job, but that’s just because he’s the first in his family to go to college and he doesn’t even know the world he’s best suited to even exists. He’ll get the STEM degree, but he won’t stop there, and he’ll find his place in the world where complex thought justifies itself.

Taylor is brilliant. I don’t know the absolute number of National Merit Semi-Finalists that are poor, first-generation children of immigrants coming from a non-English speaking home, but I’m sure it’s appallingly low. He can read anything—not just decode, but understand nuance and tone and context. He writes organized, effective prose. Taylor has barely begun to tap his own potential—even here, I’m not sure he’s ever really had to put his head down and work. Outside projects, like Robots and Academic Decathlon, have given him the opportunity to really extend himself, but even then he’s been working off of someone else’s blueprint, and that’s not the same. This is one that is going to explode a few years into a true intellectual.

Taylor likes to talk, but not in a large class. He’s best in a small group, or during office hours: he’s the sort that thinks so fast that he needs to speak slowly—any question posed to him evokes not a response, but a mental avalanche of responses, objections, counter-responses, analogies, and implications that he needs to process before he talks, needs to almost physically keep himself in check to insure that he isn’t leaving his listener far behind. His essays were fantastic— Taylor at his best when he has time and space to really develop an idea. While Taylor certainly has a breadth of knowledge to draw upon, in his heart he is a deep thinker—he wants to take ideas and see how far he can go with them. He’s just the sort that thrives on really complex and intricate research.

It would be easy to mistake Taylor for being a little cold. He worries he is a little cold, because it is very clear to him that he has more control over his external emotional reactions than the average teenager. But he’s not—he’s cerebral, definitely, and he values rationality, but he also has a great sense of humor: Taylor was the only kid in class that caught my most sophisticated jokes, and his subtle half-grin of approval always made me feel like I’d accomplished something. He can be incredibly intense when he is intrigued by a new idea, and he knows how to listen, really listen, when he’s hearing something new. He also can be moved to anger on rare occasions—he doesn’t yell or wave his arms, but Taylor is sensitive to cruelty and thoughtless ignorance. He is well liked, and has a circle of friends, but he struggles to connect easily to his peers as a whole—he’s not given to adolescent banter. But when he feels safe—when he doesn’t worry he’s talking over someone’s head or boring the life out of them--he’s fantastic: warm, engaged, thoughtful and willing to listen. He likes this school and he likes his classmates, but he hasn’t quite found his people yet. I’m pretty sure that he will find them in the world of academia.

Taylor is really special. I am quite fond of him, and absolutely convinced he will make meaningful contributions to the stock of human knowledge. He carries my strongest recommendation.

If you have any questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Sincerely,

Amanda Ashmead, Humanities Chair

Example Recommendation Letter - The Traditional Approach:

The Middle-of-the-Pack Student

To whom it may concern:

I have such a soft spot for Jordan. In the year he was in my AP Literature class, I really learned to respect his unusual ability to reflect on his own life, and to use his own self-reflection to set goals and expectations that are meaningful and appropriate to who he is, not merely a response to others’ expectations.

In most any high school in America, Jordan would be an academic superstar. Here, at an exclusive STEM magnet, he’s very solid middle. This is a difficult adjustment for many students, and many of them handle it poorly. They make excuses, or they get discouraged, or they start slacking off so that they can pretend they never wanted success in the first place. Jordan did none of that. He recognized pretty early that he was going to have to work very hard just to keep up with the pack, and so he buckled down and did that. Again, I want to reiterate that “middle of the pack” is still more advanced than what any normal school offers—not just taking and passing multiple AP STEM classes, but opting into challenging humanities electives as well.—but here, that feels like a lot of work to be nothing special. Jordan wasn’t at all discouraged about that—his goal has always been self-improvement, not using others as a yardstick. In one of his college essays, he talked about how maturity is about endurance, and putting one foot in front of the other even when it seems like the ultimate goal is out of reach. Jordan figured that one out entirely on his own, and I tend to think a young man who understands that simple truth is well nigh unstoppable.

While Jordan might have been middle of the pack in his STEM courses, he was one of my better English students. His observations and insights into characters in great literature were always impressive, and grew better and better throughout the year as he learned to appreciate the medium more. I always noticed that he was unusually sensitive to character’s internal struggles and doubts, their unspoken motivations. His essays and classroom commentary often presented very clever ideas that were totally unrelated to my own interpretations or previous class discussions. I think this is an outgrowth of his tendency to intensively reflect on his own motivations and internal processes. His own personal aesthetic is a wonderful combination of STEM-nerd, gentle vaquero, and small town friendly. That’s absolutely something he constructed himself out of his own reflections and what suits him, because nowhere in the world combines all those world-views.

Jordan is also a very fluent writer. The structure of AP exams works against him here—Jordan is a think-write-think-write type, and AP exams are about disgorging facts and analysis in a rough draft, showing you can produce the ideas in a hurry and assuming you can refine them later. For Jordan, refining is part of the thinking process and he can’t do the one without the other. I think this held him back significantly, and that he will really thrive in college where the extended researched argument becomes the standard product. Jordan’s brain was made for extended researched arguments.

Finally, Jordan is a sweetheart. He’s so nice, so intensely sympathetic to others. He’s had some rough knocks in his life—a terrible divorce, and a mother that I think has not coped with that well. He’s been largely on his own in terms of direction—everything he’s accomplished has been the product of his own ambition and ability to figure things out. I am a worrier by nature, but I don’t worry about Jordan Moreno: he’s proven his ability to be successful. I will miss him. Jordan carries my strongest recommendation. If you have any questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Sincerely,

Amanda Ashmead, Humanities Chair

Example Recommendation Letter - The Traditional Approach:

The Outlier Student

To whom it may concern:

You look at Jordan’s application, and the story writes itself—fantastic test scores, pathetic grades, weak extracurriculars--anyone would look at those and think “smart, but doesn’t apply himself—will huddle in his dorm playing video games until he flunks out. Next!” That’s the obvious, easy interpretation—it’s how a lot of us interpreted him, for years—but it couldn’t be further from the truth. Please, please, please take a deeper look at this application and consider giving him the chance he needs to demonstrate the amazing young man that he is.

First, bluntly, Jordan is a victim of sustained abuse. CPS has been called, the situation has been mitigated, we are watching him, but by the time we became aware of this, much of the damage had been done. As a freshman, he sat in my class with a flat affect and refused to answer questions or do homework. He often looked exhausted. I assumed---we all assumed—he was a student who really didn’t want to be in our specialized STEM program and he was committing academic suicide so that he could return to his home school. I did ask if there was anything wrong at home, but he very convincingly blew that off. It wasn’t until his sophomore year that the situation was revealed to us, and even then, it came in bits and pieces—he kept talking about “corporal punishment” and really didn’t seem to understand that bruises up and down your arms and knees stiff from hours of kneeling were not a “dark quirk of culture”--which was how he rationalized this to himself. The abuse came entirely at the hands of his father, and while the physical punishment has stopped, it is still not a happy or healthy household. Jordan has learned some hard lessons at his father’s hands, and they continue to affect him.

First, Jordan is a stubborn son-of a-bitch. He has a perfect poker face—I think you could cut his fingers off and he wouldn’t flinch. That stoic face is his way of deflecting others, of avoiding notice or interaction, but it’s also his way of not giving in to his father—in a situation where he had no control and no way out, he at least made sure not to give anyone the satisfaction of seeing him hurt. I admire that in him, but it worked against him here: we didn’t reach out as quickly as we should have, we didn’t push him enough, because we didn’t really think he gave a damn about anything. It’s a mistake that haunts me. But at the same time, I know that rock-solid perseverance will be an asset to him. His perspective on what counts as a “challenge” is entirely different from other students his own age, and while I’m sure he will face real challenges as a student and as an adult, he will have the unimaginable luxury of being able to respond to those challenges, to act. After what he has been through, he will always see that opportunity as a gift to be taken advantage of.

There are other lessons I wish he hadn’t learned so well: he’s been taught that he isn’t entitled to anything—not love, not support, not safety. It stops him from asking for help when he should, and it’s going to be a long path for him to learn that he’s allowed to expect things from the people that love him. He’s learned that strength is about enduring, not advancing—his hero is his mother, a war refugee who has fought her whole life to survive. His own situation is exasperated by his father’s emphasis on success: every ambition Jordan ever developed—from spelling bee to karate to academic success—turned into a justification for rage and abuse when he “failed”--and it didn’t matter how far he advanced, as long as there was anyone anywhere who achieved at a higher level, he was made a target. I have no doubt Jordan will be successful at school, in the sense that he will graduate in 4 years with reasonably good grades. I hope for more, though— that he will find a community that teaches him that it’s safe to want things, to fight for them.

He’s very slowly opening up to a few of us, and we’re discovering a wonderful young man. Even when he appeared to be a sullen 14-year old, I liked him, though I couldn’t have told you why—mostly I liked the way his face and body language reacted when we discussed literature, because it was the sort of reaction that showed me he was sensitive, sympathetic, and sophisticated in his worldview. He also genuinely loves learning: his SAT scores show you that he’s plenty capable, but the AP scores show more—that even when he couldn’t do homework, he always wanted to learn and understand. Even when he was staring off into space, he was paying attention. He’s passed seven AP exams already--and the two he didn’t pass were taught by teachers who are . . . strongly authoritarian, which did not encourage his best. He has a fantastic sense of humor; it’s hard to make him smile—but when he does, it’s in response to something truly clever.

Jordan is going to break this cycle and turn into the sort of person who speaks out against the sort of hell he faced. He has so, so much to give if only we can get him to a safe space where he can undo some of the damage done to him and start to rebuild himself. If you have any questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I mean that.

Sincerely,

Amanda Ashmead, Humanities Chair

Another Outlier Student Example

To whom it may concern:

Taylor is a bit of an anachronism. He’s been raised by his grandparents using a model that was honestly a little old-fashioned when they were raising their own kids: it’s all early to bed, early to rise, plenty of chores, and you aren’t going to spend all summer sitting around young man, you can be chopping wood and mowing lawns to save for college. There was also a great deal of unconditional love and mutual respect. Together, that combination has shaped a strong-minded, hard-working, ethical and rational young man who manages to be both socially awkward and oddly charming.

Taylor has an interesting brain. He soaks up information like a sponge, reading at the very highest level: he has an enormous, robust vocabulary and is comfortable with long and archaic texts. He reads the way a person reads when raised by grandparents who didn’t believe in screentime and who were happy to find him some chores if he were bored. He talks all that information and files it away in some crazy system, the cognitive equivalent of a Mad Scientist’ journals. I know this is true because he makes connections that are at times brilliant, at times spurious, and always interesting. He processes everything through quirky analogies, odd comparisons, and non-intuitive connections. When the connections are spurious, he’s very polite and very willing to listen to the counter-argument, but never blindly accepts someone else’s point of view—Taylor has to come to his own understanding. Luckily, all that information and all those connections mean that his own understanding is very complex, and while he at times gets lost in the forest of his own vast mind, he always finds his way back.

Taylor’s incredible ability to read is matched by a strong narrative voice: he’s a good writer. Here, again, there’s a tendency to organize information in a way that’s somewhat counterintuitive—the order that makes sense to him, his sense of what is important and what is detail—is sometimes a little non-typical, but there’s an undeniable brilliance there and a strong natural voice. I always genuinely looked forward to reading his essays. He’s much more interested in ideas than in people: even in literary analysis he always wanted to quickly bypass questions of character and motivation and get into the really complex abstract ideas underlying the personal.

Taylor is a hard worker with absolutely no expectations of short-term gratification. He’s very willing to set a long term goal and work toward it in stages, and supremely confident that if the plan is good and he does what he needs to do, it will work out in the end—however far away that is. He was raised in a household where hard-work and self-reliance and general competency were important virtues, and he’s adopted that worldview without hesitation.

Taylor would be a wonderful addition to any academic community. He’s absolutely academically on par with any of his peers, but his background, his frame of reference, his sense of how things connect is so unique that he can’t help but inspire true intellectual dialogue. He’s patient and polite and respectful and he truly loves to learn. I highly recommend him.

If you have any questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to contact me.

Sincerely,

Amanda Ashmead

These are great, but I’d like to shake things up. Is there another way?

Yes! And it’s about dang time.

The Organized Narrative Approach to Writing a Recommendation Letter for a Student

In the 1600s, if you knew Greek and Latin, you could get into Harvard (semper ubi sub ubi, y’all). And while the college application process has changed since then, we’re still using the traditional letter of rec format that Ralph Waldo Emerson used to refer Walt Whitman in the 1860s. In the words of the modern prophet Post Malone, it’s time to make things “better now, better now.”

Our buddy Chris Reeves, his buddy Trevor Rusert, and their colleagues crafted what they call the “organized narrative” style of rec writing, which “allows writers to quickly and effectively draft personal and detailed letters using a hybrid of headers, narratives, and bullet points.” The style is focused and fast—both to read and to write. (Another perk: You won’t have to bother with those persnickety transition sentences. Boom!)

Below, we show what the format looks like for teachers.

The organized narrative structure is broken into these parts:

Student’s Experience with the Curriculum

Start with a narrative that introduces the class you teach, and your student as a student in that class. Keep this to one or two paragraphs.

Academic and Intellectual Growth

Bullet points, baby. This is where you write, in one-two sentences for each bullet point, about how the student has grown in your class, their strengths and weaknesses, their intellectual vitality, etc.

Personal Qualities

Again, bullet points. What is this student like as a person? What’s their personality? Character? How do they treat their peers? What about them makes them more than simply a “body in a chair” to you?

Final Recommendation

This is the part where you wrap things up in a sentence or two and write just how much you recommend the student.

Need proof it works? Here’s what a few admissions offices had to say about the new style (also taken from a slide at a presentation that Chris and Trevor gave at the 2017 NACAC Conference):

Bowdoin:

“I really like the format, especially starting with the narrative at the top of the letter—it offers context for the rest of the letter. I like bullet points. I’m very visual that way, given reading 20 apps/day, the less work my brain has to do in a day, the better for me.”

Notre Dame:

“The format is great—it actually helps guide the reader. Even if it goes on to two pages, it doesn’t feel like a two-page letter. The format is nice.”

Providence College:

“The bullet points are very helpful. The writer gets right to the point and is focused on the heading. When reading so many applications, I would prefer this format over the narrative letters.”

University of Richmond:

“We really like it! We’re huge fans of organization that centralizes thoughts and minimizes rambling.”

Washington University in St. Louis:

“It is easy to find what I am looking for. We look for personal qualities and the format is ideal for providing this information in a reader-friendly way. The format highlights a student’s contributions in class, the hallway, etc.”

Example Recommendation Letter - The Organized Narrative Approach

Want to see these teacher letters in the wild? Michelle Rasich, director of college counseling at Rowland Hall, helped curate these examples—feast your eyes.

In a nutshell:

Here’s Chris: “Ultimately, using an organized narrative style of letter eliminates the need for counselors and teachers to worry about things like style, creativity and prose, and allows them to focus on the things that really matter to college admission professionals—relevant information about the student.

Okay, I’m ready to write. But ... what if I don’t know the student very well?

Click here. Send this form to your students or print out the PDF and have them fill it out by hand. #oldschool

That’s a wrap.

Congratulations—and phew! You’ve made it to the end of our guide.

Before you fall over from the mental food baby we’ve given you, we’d love to hear from you. Is there something we’ve overlooked? Something that can make this guide better? Maybe you’ve got another suave rec letter format you’d like to share. Email us at help@collegeessayguy.com.

Finally, if you’re feeling inspired and want to learn more about all things college-admissions, we’ve got you covered—find your next free guide here. If you’re still curious, you can also check out the student and counselor versions of this guide. Happy reading!