Written with Amanda Miller (financial aid advisor) and Jodi Okun (financial aid consultant at Occidental College and Pitzer College and author of Secrets of a Financial Aid Pro)

In this post, we’ll cover:

What a financial aid award letter is and why it’s important

How to find your award letters if you don’t already know where they are

How to read what’s on your award letters and compare across schools (using a handy tool) to determine how affordable each college will be

Some last important tips about college affordability

How to write a financial aid appeal letter (if you need to)

You’re in! Congratulations. You’re in that sweet spot between the joy of acceptance and the reality of the college workload. Soak it in.

Ever since you received your acceptance you’ve been bombarded by your schools asking you to “submit your deposit.” And while you definitely do not want to miss the May 1 deposit deadline (seriously, they will give away your spot), you generally don’t need to commit to a school any earlier than May 1--and you definitely don’t want to commit before you’ve got all the facts about financial aid.

Notable exceptions are those who applied Early Decision and athletes who’ve signed National Letters of Intent. Once you’re in, that’s where you go.

Also, beware about earlier housing deposit deadlines. (These are set by residence life, not the admissions office.) Many colleges will extend this deadline, if you ask them, though. And any deposit made before May 1 should be refundable if you ask for a refund on or before May 1. #OpenLineOfCommunication

So how do I figure out how much the schools I was accepted to are actually going to cost?

Step #1: Find your financial aid award letter.

By April of your senior year, each college granting you admission and applied financial aid will send you a document called your Financial Aid Award Letter. This will arrive via email or snail mail. If you’re unsure how to find it, call the college’s Financial Aid Office to ask how they sent it. Better yet, ask them to guide you to it electronically while you’re on the phone. Yay self-advocacy!

Pro Tip: Any time you speak with your college’s financial aid office keep a record (in the Notes application on your laptop or somewhere else you won’t lose it). Include the name of the person with whom you spoke, the date, and what they said to you. Most of the time you won’t need this, but it’s better to have insurance against bureaucratic kerfuffles just in case.

WARNING!

Did the financial aid office say they don’t have an award letter ready for you because they’re missing important financial documents or because you’ve been selected for “verification”? Yikes! This needs to be resolved ASAP so you know how much you’re getting in time to decide before May 1!! Stop what you’re doing and get on this, like, right now.

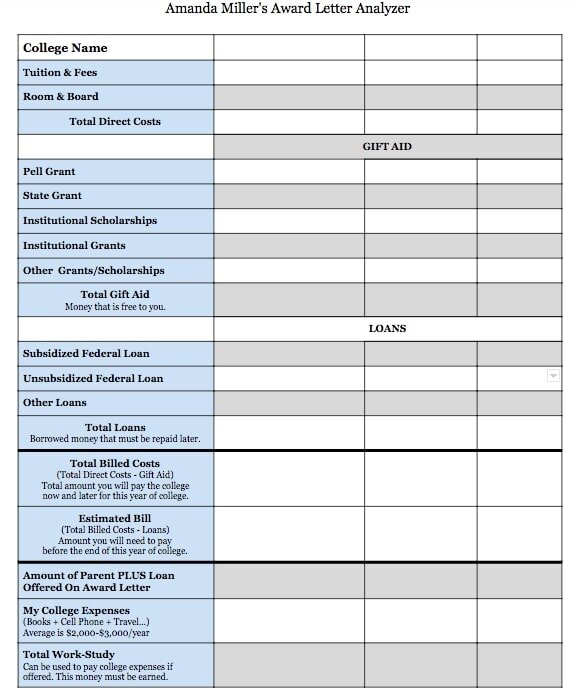

Step #2: Fill out Amanda Miller’s Award Letter Analyzer

Almost every award letter looks different, which can make it difficult to compare across schools or even understand what the letter is actually saying. This is why a tool like the Analyzer is super helpful. You’ll find a copy here, with line-by-line guiding tips below on how to fill it out.

Useful for college and good practice for filling out tax forms! #Adulting

How to Fill Out Your Award Letter Analyzer

Cost Section

Tuitions & Fees: Tuition is a given, though it may not appear on your award letter. If it doesn’t, look it up for the upcoming school year. (Tuition generally increases a little every year.) Fees cover all those “free” amenities on campus: “free” athletic tickets, “free” gym, “free” tech support, “free” counseling center, “free” concerts, etc. There can also be extra lab fees for STEM classes. One fee you can generally get taken off is the health insurance fee, as long as you submit proof you are on your parents’ insurance plan. Also, optional add-ons like parking stickers are usually not included.

Room & Board: These costs can have some flexibility. If you live in a suite or have a single room, your housing will be more expensive. Most colleges require those who live on campus to have a meal plan. My advice is to downgrade from the unlimited meal plan as soon as possible. No one needs that much food unless they are an athlete, only eat in the dining hall, or wake up every morning before class to eat a giant stack of pancakes.

Pro Tip: Many schools will let you apply for a resident advisor (RA) position after your first year. This can not only reduce housing costs; in some cases you can sometimes make money for living there. Consider becoming an RA if you enjoy organizing ice cream socials and don’t mind politely policing other forms of recreation.

Total Direct Costs: Add up your Tuition & Fees and Room & Board lines. This is how much your first year will cost before financial aid. (Gasp!) Colleges may completely omit cost information on the award letter. Or they may provide an exhaustive list, including indirect costs like travel (read: airfare/gas money to get there), personal expenses (movie tickets, deodorant, etc.), and books & supplies. While you do have to pay for those indirect costs, they will not be billed directly by the college.

Gift Aid Section

Pell Grant: A Pell Grant is a free federal grant you received because a) you filled out the FAFSA and b) you qualified. If you check your FAFSA Student Aid Report (SAR), you will either see Pell Grant with its amount listed or you will only see the standard federal loan.

State Scholarships/Grants: These can be a little tricky to figure out, but don’t sweat it. If the award letter says something about a “grant” or “scholarship” with the name of your state attached to it, it probably goes here. Again, the link to find out about your state’s aid program is in the Treasure Trove. If you think you’re eligible for something that’s not on your award letter, check with your college’s financial aid office. They may be waiting on the state for final numbers but can likely give you a solid estimate.

Institutional Scholarships/Grants: Scholarships are the free money you’re receiving from the college because you’re awesome and they want your awesomeness at their school. Grants are the free money you’re receiving from the college because they want to help you make their school more affordable. (We mostly see these from private colleges.) Either way, it’s free money!

Other Scholarships: Did you apply for and win any of those local scholarships through your high school? Or an online scholarship? Employers, unions, fraternal organizations, and community organizations are the most common sources of “outside” scholarships. Record all those outside scholarships and any other type of free funding you will receive outside your family here.

Beware: Some colleges deduct outside scholarship dollars from your institutional aid! Be sure to ask your financial aid office if your outside scholarships will “stack” on top of the aid they’ve already given you.

Total Gift Aid: Add up all your gift aid and put that amount here. Don’t sweat whether you got the right things on the right lines within this category. The total will be the same. What is important to know is how you received the money and how to make sure you get the money again next year.

Don’t assume it will be the same each of your four years. Make sure by talking out any questions you have with your college’s financial aid office. You’ll be amazed how much heartache and confusion this will save later!

Loans Section

Subsidized/Unsubsidized Federal Loans:

Everyone who fills out a FAFSA is offered the option of taking out unsubsidized federal student loans. What can differ is whether or not you are offered a subsidized loan.

What’s the difference?

A subsidized loan is a loan that the federal government pays the interest on while you’re in college (and for a few months thereafter).

An unsubsidized loan is a loan that accrues interest (gets bigger) while you’re in college.

The maximum loan (of both there types together) a student can take out for their first year is $5,500. The maximum allowed increases each year.

These loans are also typically “deferred” loans, which means you don’t have to make payments on them until you’re done with school. This includes graduate school, medical school, etc.

Other Loans: Only a small percentage of student borrowers arrange for outside private loans from a bank or other institution because they tend to have higher interest rates and require a cosigner. Before getting an outside loan, check the lender’s interest rate against the federal rate.

Total Loans: Add up all your loans.

Pro Tip: Loans aren’t automatically dispersed. You can refuse them and pay the amount out-of-pocket instead. If you do decide to take out any federal loans, you’ll need to do two things:

Entrance Counseling: an online module to make sure you understand how loans work, and

Sign a Master Promissory Note: a binding legal document saying that you, the student, will pay back this money after you graduate.

You can complete both of these steps on the federal government’s student loans website, conveniently named studentloans.gov.

Now for some math. Don’t worry. This is calculator-active.

Equation #1: Total Direct Costs - Total Gift Aid = Total Billed Costs

Total Billed Costs: This is how much you will eventually pay (with interest if you’re taking a loan) for your first year at this college. Multiply by four and you’ll get a ballpark of how much your college degree will cost at this school.

Bear in mind, tuition tends to increase every year, and the percent of need met can decrease after first year for a number of reasons including not meeting Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) and a regressive policy that some colleges practice called "bait and switch."

Equation #2: Total Billed Costs - Loans = Estimated Bill

Estimated Bill: This is how much you have to pay (or arrange to pay) before the end of your first year of college. Typically, it’s split into two payments: one due in August and one due in December/January.

Families can set up monthly payment plans starting in the summer. Talk to your college’s financial aid office to investigate this option by no later than June 30th before you start.

Bonus equation: Divide your Total Billed Costs by 10. That’s how many hours you’d have to work a $10/hour job to pay for this one year. So don’t skip class!

Now for some odds and ends...

PLUS Loans: These are federal loans that parents can apply for to help them pay for their child’s college expenses. Most parents with decent credit are eligible, however, and just because it’s listed on an award letter doesn’t mean the money’s guaranteed. The dangerous aspects of these loans are twofold. First, eligible parents can borrow enough to cover the cost of attendance minus your gift aid and student loans; but this is likely way more than you could possibly need to pay the bill. Second, the interest rate is higher than that of a student loan. These factors combined can get families into a lot of trouble if they don’t have a clearly defined plan to repay the money. While these options may be okay for a little assistance, hopefully, this book has helped you find a college that doesn’t place a heavy financial burden on you and your family.

My College Expenses: Your college includes things like books, personal expenses, and transportation when they calculate the Cost of Attendance. Just because your college doesn’t charge you for these things directly doesn’t mean they don’t cost money. Each college usually provides an estimate of these expenses, but these estimates may be way off for your situation. Add up for yourself (and maybe ask for parent advice about) how much you will need to budget for the following:

A new laptop/device and its accessories

Books & materials like pens, notebooks, etc.

Gas/airfare to get from your home to campus at least four times

Spending money

Toiletries (deodorant, shampoo, Tylenol, bandaids, and all those other items stocked under your bathroom sink)

Dorm room furnishings (a powerstrip, a light, a rug, those weird-sized sheets)

Add all these expenses up. Be ready for the “you need a summer job” talk.

Work Study: Federal work study is a government-funded program for students who qualify to work on campus in order to earn money for college. (How do you qualify? You guessed it. FAFSA.) If this isn’t on your award letter, it doesn’t mean you can’t find a job on or around campus to fund your expenses from the previous section. It just means you won’t be guaranteed an on-campus job when you get there. If this is on your award letter, it’s important to know two things: 1) you need to make sure you figure out how to get connected to a job on campus as soon as you get there, and 2) Ninety-nine percent of the time, this money is deposited into your bank account (instead of being deducted from your college bill), meaning you can spend it one whatever you like...Be smart and save though, because that money can help pay for next semester.

Did we miss something? Is there something on your award letter that doesn’t seem to fall into any category described above? Call your financial aid office for clarification.

Okay, so you’ve filled out your award letter analyzer...

How does it look? Are your schools roughly equally affordable? Or are some way cheaper than others? Does this influence your decision about where you might go in the fall? Talk this over with your family to make sure everyone’s on the same page.

- The national average for total student debt incurred to earn a bachelor’s degree hovers around $28,000.

- ⅔ of your starting salary is generally accepted as a reasonable amount of college debt. A teacher making $30,000 could have up to $20,000 in debt. A petroleum engineer making $60,000 immediately upon graduation could be $40,000 in debt. If you’re not sure what you’ll end up majoring in, aim to stay under the $25,000 mark.

- Obviously the less debt, the better, but don’t feel that you haven’t “won” or you’re “in trouble” if you end up taking a standard federal student loan.

If you’ve completed the steps above, you now understand your award letters and how much you’ll be paying for each school.

But what if the school you’ve decided you want to go to most isn’t financially feasible?

Two options:

Rejoice that you put great fit financial safeties on your list and happily submit your housing deposit to one of those schools!

Write a financial aid award appeal letter to that first choice college asking for more aid. How? Like this:

How to Write a Great Financial Aid Award Appeal Letter

So you’ve been accepted to a great college (yay!) only to find out the school isn’t giving you enough money (womp womp). What do you do? Accept your fate? Resign yourself to attending your back-up school? Start a GoFundMe campaign?

Maybe. But first...

You gotta’ wonder: Is this ALL the money the school can offer me? Could it be that, if you ask nicely, the school just might give you a little more? Did they miss something important in your aid application, for example, or did you fail to explain a change in circumstance adequately?

Maybe.

True story: When I asked Northwestern for more money the school gave me more money and THAT LED TO THE BEST FOUR YEARS OF MY LIFE. In fact, I only spent about $4,000 per year. Caveat: I had a zero EFC (Estimated Family Contribution), so much of it was need-based aid, but still! If I hadn’t asked, I wouldn’t have gotten more money and probably wouldn’t have gone there.

You should also go ahead and do it because:

you can write an appeal letter in like an hour

it may be the fastest $2,000 (or $8,000) you ever make

if you don’t ask, you’ll never know.

When should you write an appeal letter?

As soon as you receive your financial award letter. Because when the money’s gone, it’s gone. So, like, now.

How do you write one? Like this:

To the Financial Aid Office at UCLA:

My name is Sara Martinez and I am a 12th grader currently enrolled at Los Angeles Academy. First, I would like to say that I am much honored to have been admitted into this fine school, as University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) is my number one choice.

Notice how she reiterates a) who she is and where she’s from, b) how grateful she is to have been accepted and c) (most important) that UCLA is her number one choice… a school likes to know this if it’s true.

There is a problem, however, and it is a financial one.

Notice how she uses her transition sentence to set up what this letter is going to be about. It’s really straightforward and explicit. Your letter doesn’t have to be fancy; it has to be clear.

I’d love to attend UCLA--it’s near home, which would allow me to be closer to my family, and the Bio department is phenomenal. But, as a low-income Hispanic student, I simply don’t feel I can afford it. I’m writing to respectfully request an adjustment of my financial aid award.

Great. First, she offers two specific reasons that UCLA is the right fit for her, so the financial aid officer understands why UCLA is her top choice. Next, she makes her request really clear: give me more money! And she does so in a straightforward and respectful way. She doesn’t beg; she asks.

Here are some more details of my financial situation. Currently, my father works as an assistant supervisor for American Apparel Co. and he is the only source of income for my family of five, while my mother is a housewife. The income my father receives weekly barely meets paying the bills.

It helps to give details of your specific family situation even if you gave these details in your original application, since the financial aid officer may not have your entire application right in front of them at the moment. Save them the work!

My family’s overall income:

Father’s average weekly gross pay: $493.30

Father’s adjusted gross income: $27,022

Our household expenses:

Rent: $850

Legal Services: $200

Car payment: $230.32

Again, specifics. Don’t be shy. Give them these numbers so that, when they do the math, that they can see what you see: there just isn’t enough money.

My parents cannot afford to have medical insurance, so they do not have a bill that shows proof of medical insurance. My father’s average monthly income is an estimate of $1,973.20 (see attached pay stub). When household expenses such as rent, car payment, legal services, gas bill, and electricity bill are added together the cost is of $1,402.70. Other payments such as the phone bill, internet bill, and groceries also add to the list. But in order to make ends meet my father usually works overtime and tailors clothes for people in our neighborhood.

Notice how she has already included her dad’s pay stub which, again, saves time (and schools might ask for things like this to verify). Also, she briefly explains the other costs (keyword: briefly) and how her family is already doing everything it can.

My family is on an extremely tight budget and unfortunately cannot afford to pay for my schooling. I have worked my way up and was recently awarded Valedictorian for my class. My goals and my aspiration of becoming a nutritionist have helped me push forward. I appreciate your time in reconsidering my financial aid award. I’m looking forward to becoming a Bruin.

Bonus info: She is VALEDICTORIAN! This is also a mini-update, as she wouldn’t have known this at the time she applied (November) but did know by the time she wrote the appeal. If you have 1-2 more updates to include, go ahead and include them here--but don’t go too crazy. You don’t want to seem desperate; you want to close strong with your most important updates.

Regards,

Sara Martinez

No fancy ending, just your basic sign-off.

You may be wondering:

Is it okay for a parent to write a financial aid appeal letter?

Yes. While college admission officers generally like to hear directly from students on a variety of things, sometimes a parent has information a student simply doesn’t have. In those cases, it’s okay for a parent to write the letter--in fact, sometimes it’s better.

Here’s an example of an appeal letter written by a parent:

Dear Financial Aid Office,

We appreciate you offering our son Paul a scholarship, but even with your help we can not afford the tuition. We have asked his grandparents and uncles to help, but they too unfortunately are not able to help pay the tuition. I would use our retirement money for him to attend your school, if we had any retirement fund. We honestly don't know how to make this happen without your help. Next month I will be having a necessary hysterectomy and I will be out of commission for a couple of months and can not work. I am a first-grade teacher at a small church school with a very small income and we can barely make ends meet.

Your school is the only school Paul wants to attend. He said to us he will not go to college if he can not go to The New School. None of the other schools offer what The New School can offer him. He has always wanted to be an actor, writer and director ever since he was five years old. Not only will Paul benefit from attending your school but you will also benefit. If you can offer us more financial help, Paul will be able to attend and graduate as one of your success stories.

Thank you in advance for taking the time to reconsider the amount you have offered Paul.

Sincerely,

Gina and Tom Atamian

Again, pretty straightforward. You may have thought that writing one of these appeals was going to involve some kind of added magic, but you know what the two more important qualities are when it comes to writing them?

Information. Give the school the information it needs to make a new decision. Bullet point this so that you don’t find yourself worrying about “how” to say it.

Actually writing and submitting the letter. I’ve seen many students that could have appealed but didn’t out of fear and ultimately they didn’t submit a letter. Just write it. If you have reason to appeal, do so. I tell my students: you don’t want to look back years from now and think, “I wonder what would’ve happened if…” Dispel those future doubts. Start with bullet points. (Yes, now.)

Want more? My podcast interview with Jodi Okun covers everything from “The Pause” before the appeal (super important) to how financial aid offices make decisions. Find a link in the Treasure Trove.

Links:

A downloadable copy of Amanda Miller’s Simple Award Letter Analyzer

The link to a site that “decodes” your award letter into three categories: grants/scholarships, work study, and loans.

The link to find out more about your state’s financial aid programs.