I frequently have students tell me that they’ve faced some challenges they think might make for a good college essay, but they aren’t sure how to gauge the strength of their topic, and they aren’t sure how to write a college essay about the challenges they’ve faced.

And those questions and confusion are understandable: While high school has probably helped prepare you to write academic essays, it’s less likely that you’ve spent much time doing the kind of personal and reflective writing you’ll want to do in a personal statement focused on challenges (which I’ll also sometimes refer to as a narrative essay).

Even the phrase “reflective writing” might seem a little new.

But no worries—I got you. In this post, I’ll walk you through:

Differences between a college essay/personal statement and a typical English class essay

How to gauge the strength of your possible “challenges” topic

How to brainstorm your essay topic

How to structure your essay

How to draft the essay

How to avoid sounding like a sob story (Part 1: Structure)

An example challenges essay with analysis

How to avoid sounding like a sob story (Part 2: Technique)

How to know if your challenges essay is doing its job

By the end of this post, you should be all set to write.

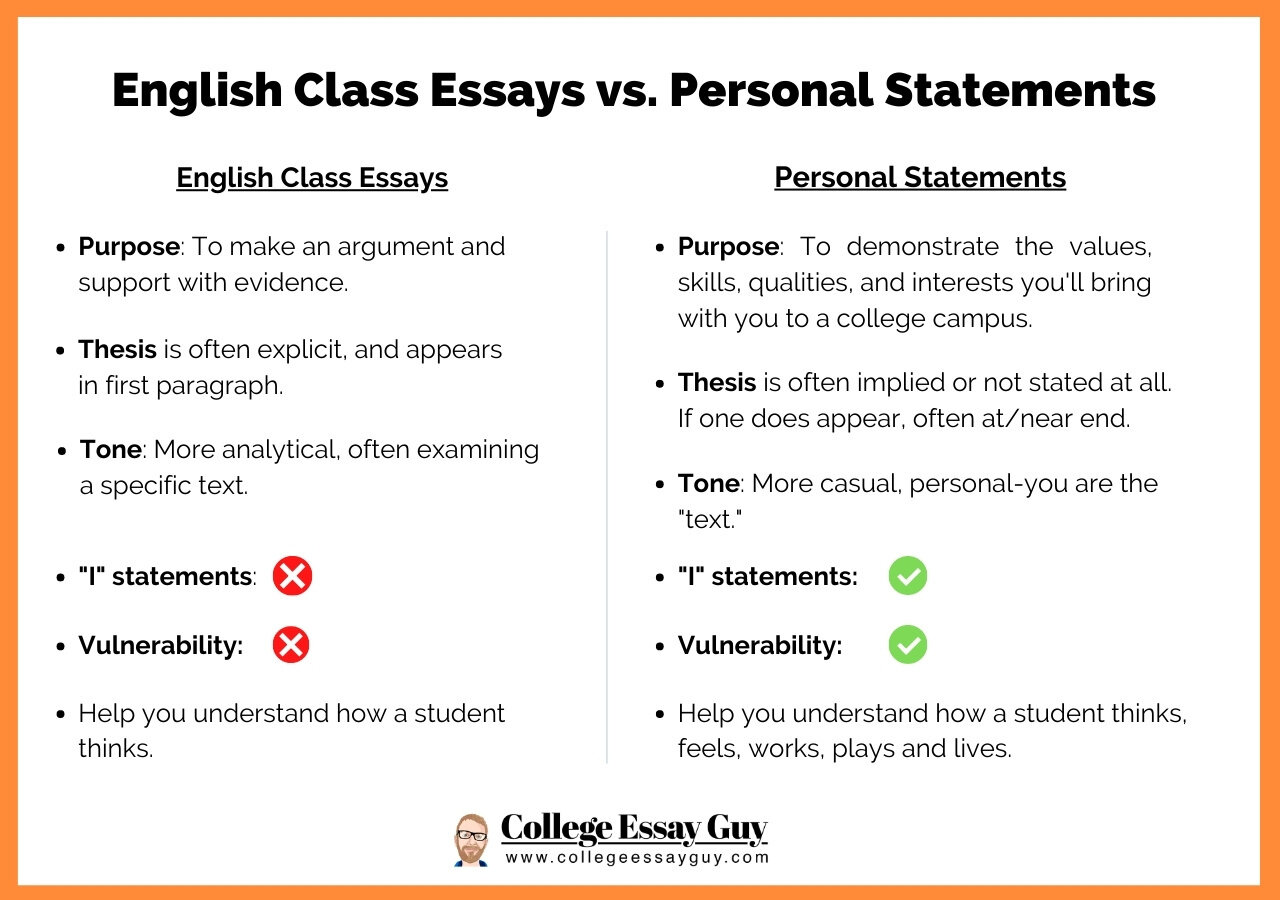

Differences between a college essay/personal statement and a typical English class essay

A personal statement is an essay in which you demonstrate aspects of who you are by sharing some of the qualities, skills, and values you’ll bring to college. This essay is a core element of your application—admission offices use them to assess potential candidates. Personal statements are also often used by scholarship selections committees (for a guide to and some great examples of scholarship essays, head here).

A college essay/personal statement isn’t the typical five-paragraph essay you write for English class, with an argumentative thesis and body with analysis.

Here’s a nice visual breakdown:

A note on forcing challenges: Before we dive into how to write about challenges, I want to dispel a huge misconception: You don’t have to write about challenges at all in a college essay. So no need to force it.

In fact, definitely don’t force it.

I’ve seen tons of essays in which students take a low-stakes challenge, like not making a sports team or getting a bad grade, and try to make it seem like a bigger deal than it was.

Don’t do that.

But you also don’t have to write about challenges even if your challenges were legit challenging. You definitely can write about strong challenges you’ve faced, and I’ve seen them turn into great essays. But I’ve also seen many, many, many outstanding essays (like many of the essays at those links) that didn’t focus on challenges at all, using Montage Structure.

Great. With all that in mind, if you feel like you’ve faced challenges in your life, and you want to write about them … how do you do so well?

A big part of the answer relates to structure. Another part has to do with technique. I’ll cover both below.

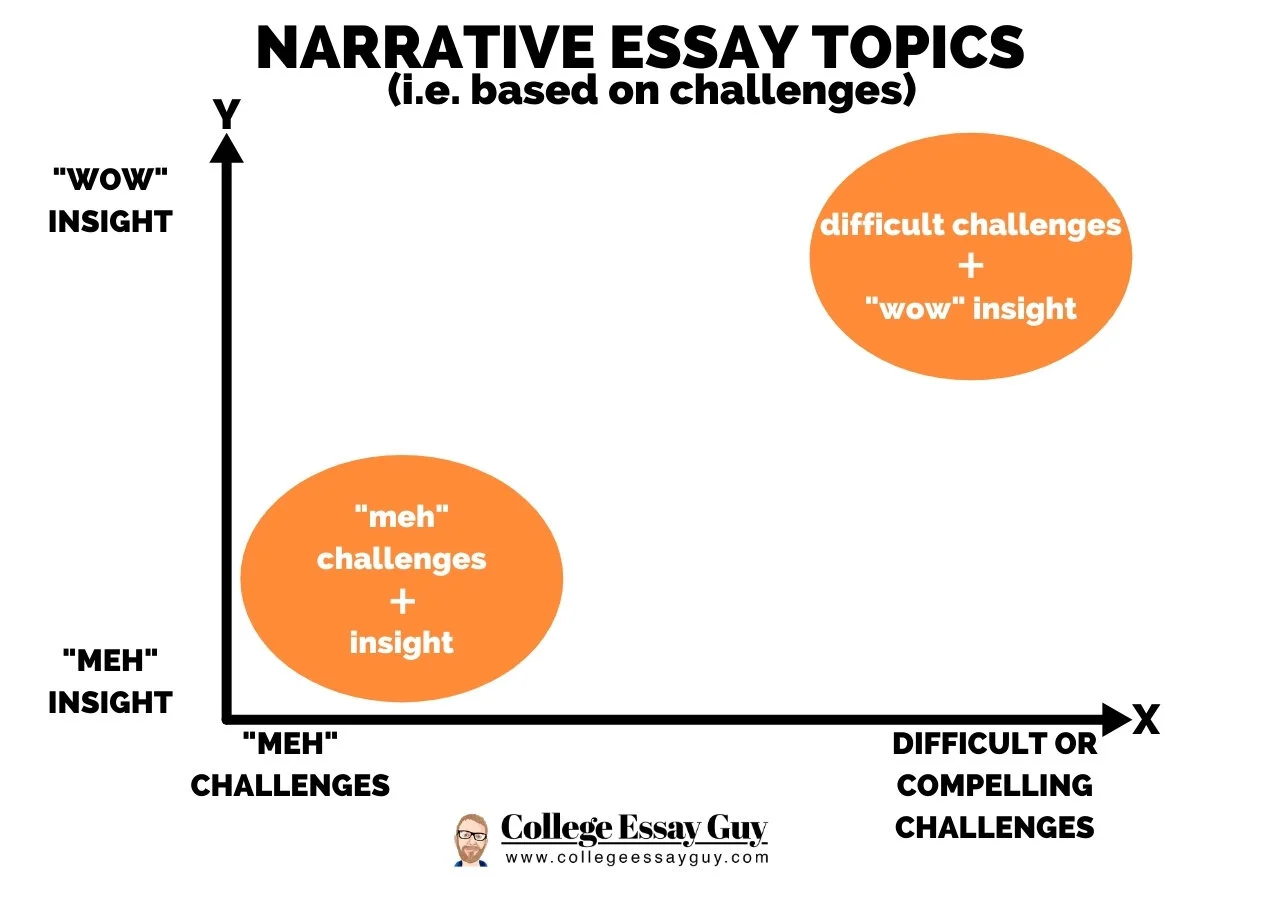

How to gauge the strength of your possible “challenges” topic

I believe that a narrative essay is more likely to stand out if it contains:

X. Difficult or compelling challenges

Y. Insight

Here’s a nice visual:

These aren’t binary—rather, each can be placed on a spectrum.

“Difficult or compelling challenges” can be put on a spectrum with things like getting a bad grade or not making a sports team on the weaker end and things like escaping war or living homeless for three years on the stronger side. While you can possibly write a strong essay about a weaker challenge, it’s really hard to do so.

“Insight” is the answer to the question, “so what?” A great insight is likely to surprise the reader a bit, while a so-so insight likely won’t. (Insight is something you’ll develop in an essay through the writing process, rather than something you’ll generally know ahead of time for a topic, but it’s useful to understand that some topics are probably easier to pull insights from than others.)

To clarify, you can still write a narrative that has a lower stakes challenge or offers so-so insights. But the degree of difficulty goes up. Probably way up. For example, the essay in the post, “How to Write a Narrative Essay on a Challenge That TBH Wasn’t That Big of a Deal,” focuses on a very low-stakes challenge, but the insights he draws and his craft are next-level, and it took the author more than 10 drafts.

With that in mind, how do you brainstorm possible topics that are on the easier-to-stand-out-with side of the spectrum?

How to brainstorm topics for your overcoming challenges essay

First, spend 5-10 minutes working through this Value Exercise. Those values will actually function as a foundation for your entire application—you’ll want to make sure that as a reader walks through your personal statement, supplementals, activities list, and add’l info, they get a clear sense of what your core values are through the experiences, skills, and insights you discuss.

Once you’ve got those, take 15-20 minutes (or more is great) to work through the Feelings and Needs Exercise.

Pro tip: The more time you spend doing good brainstorming, the easier drafting becomes, so don’t skip or skimp on those. And with just those two exercises, you should be ready to start drafting a strong essay about challenges.

How to structure your essay

Once you’ve done the Feelings and Needs Exercise (and go ahead and do it, if you haven’t), structuring your essay will actually be pretty straightforward.

Here’s the basic structure of what we’re calling the Narrative (Challenges-Based) Structure:

Challenges + Effects

What I Did About It

What I Learned

The word count of your essay will be split roughly into thirds, with one-third exploring the challenges you faced and the effects of those challenges, one-third what you did about them, and one-third what you learned.

Conveniently, you’ve already got the content for those sections because you did the Feelings and Needs Exercise thoroughly.

As mentioned in the Feelings and Needs post, the feelings and needs will be spread throughout your essay, with some being explicitly stated, while others can be shown more subtly through your actions and reflections.

To get a little more nuanced, within those three basic sections (Challenges, What I Did, What I Learned), a narrative often has a few specific story beats. There are plenty of narratives that employ different elements than what follows—for example, collectivist societies often tell stories that don’t have one central main character/hero. But it seems hard to write a college personal statement that way, since you’re the focus here. You’ve seen these beats before, even if you don’t know it—most Hollywood films use elements of this structure, for example.

Status Quo: The starting point of the story. This briefly describes the life or world of the main character (in your essay, that’s you).

The Inciting Incident: The event that disrupts the Status Quo. Often it’s the worst thing that could happen to the main character. It gets us to wonder: Uh-oh … what will they do next? or How will they solve this problem?

Raising the Stakes/Rising Action: Builds suspense. The situation becomes more and more tense, decisions become more important, and our main character has more and more to lose.

Moment of Truth: The climax. Often this is when our main character must make a choice.

New Status Quo: The denouement or falling action. This often tells us why the story matters or what our main character has learned. Think of these insights or lessons as the answer to the big “so what?” question.

Whether you want to just stick with the bullet points in your Feelings and Needs columns, or you want to also lay out your Status Quo, Inciting Incident, etc., is up to you—either approach can work well.

How to draft your challenges essay

First, outline.

Outlining will save you a ton of time revising.

And conveniently, again, you’ve already got most of what you need to build a strong outline.

Simply grab the bullet points from your Challenges + Effects, What I Did About It, and What I Learned columns from the exercise and stack them. For example, here’s a sample outline, followed by a link to the essay it led to:

Narrative Outline (developed from the Feelings and Needs Exercise)

Challenges:

Domestic abuse (physical and verbal)

Controlling father/lack of freedom

Harassment

Sexism/bias

Effects:

Prevented from pursuing opportunities

Cut off from world/family

Lack of sense of freedom/independence

Faced discrimination

What I Did About It:

Pursued my dreams

Traveled to Egypt, London, and Paris alone

Challenged stereotypes

Explored new places and cultures

Developed self-confidence, independence, and courage

Grew as a leader

Planned events

What I learned:

Inspired to help others a lot more

Learned about oppression, and how to challenge oppressive norms

Became closer with mother, somewhat healed relationship with father

Need to feel free

And here’s the essay that became: “Easter”

This is why you want to outline well before drafting—while virtually every essay will have to go through 5+ drafts to become outstanding, outlining well (like the above) makes writing a strong first draft much, much easier.

A few last tips on writing your early drafts:

Don’t worry about word count (within reason).

Don’t worry about making your first draft perfect—it won’t be. Just write.

Don’t worry about a fancy opening or ending.

If your first couple drafts of a max 650-word essay are 800 or 900 words, you’re totally fine. You’ll just have to cut some. But that kind of cutting often makes writing better.

And eventually, you’ll want a strong hook and an ending that shows clear, interesting insights. Insight in particular can be the toughest part of writing, as you may not have previously spent much time reflecting on why your experiences are important to you, how they’ve shaped your values and sense of self, and how they in essence help to fill out the bigger picture of who you are. But don’t let that stop you from writing your early drafts. Again, you’ll revise those things.

Just write.

Then revise. And revise. And revise ...

How to avoid sounding like a sob story (Part 1: Structure)

This is a common concern many students have.

If I tell you a personal story about a challenge I faced, I don’t want you to think I’m doing so because I want you to pity me.

But you also want to be able to tell a story, because one way to help us see who you are is to show us what values and insights you’ve developed through the challenges you’ve faced. So, if you have a challenge you think might make for a strong college essay, learning how to write in a way that shows a reader what you’ve been through without feeling like you’re “telling a sob story” is super important.

Here’s how to do that.

Most of how you avoid a “sob story” is through structure. Think back to what we talked about earlier:

Challenges + Effects

What I Did About It

What I Learned

Notice that two-thirds of your essay doesn’t focus on the challenges you’re facing—you focus on who you’ve become because of them. Most of the story is about what you did, what you learned, how you’ve grown.

This is why you don’t think of most movies as sob stories—because they’re not an hour and 40 minutes of details about bad things that have happened, and just 20 minutes of actions and growth.

This leads to an important note: It can be hard to write about a challenge that you’re still in the early stages or middle of working through. You can try. But it may be easier to turn that challenge into a paragraph in a montage, rather than trying to build a full essay around it (since you may not have as much to say regarding the What I Did and What I Learned aspects yet, and those are really important).

Here’s a nice example essay that uses Narrative Structure to write about challenges well. As you read it, ask yourself if it seems like a “sob story” to you.

Example challenges essay with analysis:

¡Levántate, Mijo!

“¡Mijo! ¡Ya levántate! ¡Se hace tarde!” (Son! Wake up! It's late already.) My father’s voice pierced into my room as I worked my eyes open. We were supposed to open the restaurant earlier that day.

Ever since 5th grade, I have been my parents’ right hand at Hon Lin Restaurant in our hometown of Hermosillo, Mexico. Sometimes, they needed me to be the cashier; other times, I was the youngest waiter on staff. Eventually, when I got strong enough, I was called into the kitchen to work as a dishwasher and a chef’s assistant.

The restaurant took a huge toll on my parents and me. Working more than 12 hours every single day (even holidays), I lacked paternal guidance, thus I had to build autonomy at an early age. On weekdays, I learned to cook my own meals, wash my own clothes, watch over my two younger sisters, and juggle school work.

One Christmas Eve we had to prepare 135 turkeys as a result of my father’s desire to offer a Christmas celebration to his patrons. We began working at 11pm all the way to 5am. At one point, I noticed the large dark bags under my father’s eyes. This was the scene that ignited the question in my head: “Is this how I want to spend the rest of my life?”

The answer was no.

So I started a list of goals. My first objective was to make it onto my school’s British English Olympics team that competed in an annual English competition in the U.K. After two unsuccessful attempts, I got in. The rigorous eight months of training paid off as we defeated over 150 international schools and lifted the 2nd Place cup; pride permeated throughout my hometown.

Despite the euphoria brought by victory, my sense of stability would be tested again, and therefore my goals had to adjust to the changing pattern.

During the summer of 2014, my parents sent me to live in the United States on my own to seek better educational opportunities. I lived with my grandparents, who spoke Taishan (a Chinese dialect I wasn’t fluent in). New responsibilities came along as I spent that summer clearing my documentation, enrolling in school, and getting electricity and water set up in our new home. At 15 years old, I became the family’s financial manager, running my father’s bank accounts, paying bills and insurance, while also translating for my grandmother, and cleaning the house.

In the midst of moving to a new country and the overwhelming responsibilities that came with it, I found an activity that helped me not only escape the pressures around me but also discover myself. MESA introduced me to STEM and gave me nourishment and a new perspective on mathematics. As a result, I found my potential in math way beyond balancing my dad’s checkbooks.

My 15 years in Mexico forged part of my culture that I just cannot live without. Trying to fill the void for a familiar community, I got involved with the Association of Latin American students, where I am now an Executive Officer. I proudly embrace the identity I left behind. I started from small debates within the club to discussing bills alongside 124 Chicanos/Latinos at the State Capitol of California.

The more I scratch off from my goals list, the more it brings me back to those days handling spatulas. Anew, I ask myself, “Is this how I want to spend the rest of my life?” I want a life driven by my passions, rather than the impositions of labor. I want to explore new paths and grow within my community to eradicate the prejudicial barriers on Latinos. So yes, this IS how I want to spend the rest of my life.

— — —

Structural Analysis:

First, here’s a breakdown of how the author uses that 3-part structure to effectively tell his story:

Challenges + Effects

Working to help support family

Physical toll

Caring for self and sisters

Prospects of spending life this way

Adapting to life in US

What I Did About It/Them

British English Olympics team and competition

Cleared documentation

Ran household for grandparents

Became family’s financial manager

MESA and STEM

Association of Latin American students

What I Learned

Pride in leadership

Autonomy and independence

Potential in mathematics

Personal perspective/value of cultural identity

Desire to push back against prejudice

Answer to “How do I want to spend my life?”

And here’s how the essay uses those narrative elements from before:

Status Quo: Life growing up workin in the family’s restaurant. Responsibilities. The daily toll.

The Inciting Incident: Cooking 135 turkeys on Christmas Eve and questioning if this is how he wants to spend his life.

Raising the Stakes/Rising Action: British English Olympics training and competition. Moving to the U.S. Taking on further responsibilities. Exploring MESA/STEM. Joining/leading the Assoc. of Latin American Students.

Moment of Truth: Re-asking “Is this how I want to spend my life?”

New Status Quo: New sense of purpose. Life driven by passions. Growth within community. Push back against prejudice.

There’s a lot of other nice stuff in that essay—we see a bunch of core values, there’s vulnerability in sharing his difficulties and worries, there are nice insights and reflections related to his growth, and there are some nice moments of craft, like re-raising the question about how he wants to spend his life.

But since we’re here to talk about how to write well about challenges, in particular, I’d want you to reflect on your response to what I asked you to think about just before the essay: Does it seem like a sob story?

Not really. Why? Largely, it’s due to the structure—the author uses the approach we’ve discussed in this post, focusing mostly on what he did in response to these challenges, and what he learned from them. It’s extremely hard for a story told like that to come off as an attempt to evoke pity. Rather, it feels inspiring. At least it does to me.

How to avoid sounding like a sob story (Part 2: Technique)

While structure alone can enable you to write about a challenge effectively (without sounding like a sob story), there are also some great techniques you can use to further strengthen how you communicate a narrative.

And a heads-up that two of these might seem to contradict each other. They don’t, but maybe it’s subtle. I’ll clarify after.

1. BE STRAIGHTFORWARD AND DIRECT

This is the simplest way, and it can be the most vulnerable (which is a good thing; more on this in a bit). Why? Because there's nothing dressing it up—no hiding behind artifice—you're just telling it like it is.

Personal statement example:

At age three, I was separated from my mother. The court gave full custody of both my baby brother and me to my father. Of course, at my young age, I had no clue what was going on. However, it did not take me long to realize that life with my father would not be without its difficulties.

- Excerpt from "Raising Anthony" in College Essay Essentials and inside our Pay-What-You-Can online course: How to Write a Personal Statement

Here, the author does a nice job of straightforwardly laying out the challenges she faced and the effects of those challenges. That quality of her language allows us as readers to fill in the feelings and impact around those challenges—I feel like I’m seeing just the part of an iceberg poking above the surface, while a whole world of experience lies below. And because she’s been so clear, my imagination starts filling in that world.

Here’s another nice example:

It was the first Sunday of April. My siblings and I were sitting at the dinner table giggling and spelling out words in our alphabet soup. The phone rang and my mother answered. It was my father; he was calling from prison in Oregon.

My father had been stopped by immigration on his way to Yakima, Washington, where he’d gone in search of work. He wanted to fulfill a promise he’d made to my family of owning our own house with a nice little porch and a dog.

- Excerpt from “The Little Porch and a Dog”

IMPORTANT: I know I’m repeating myself here, but it’s so important, I’m fine doing so: Most of your “challenges” essay isn’t actually about the challenges you face. That’s an added bonus with using simple and direct language—doing so allows you to set up your challenges in the first paragraph or two, so you can then move on and dedicate most of the essay to a) what you did about it and b) what you learned. So just tell us, with clear and direct language.

2. WITH A LITTLE HUMOR

Click here for a quick clip, or Google this phrase:

“Ding-dong, the wicked witch is dead.”

Someone just got crushed by a house. That’s actually a pretty dark moment.

But it doesn’t feel nearly as dark as it actually is. Because they’re singing about it and dancing.

This is something you can do in writing about challenges: Add a touch of levity (by “a touch,” I mean probably not Munchkins-singing-and-dancing level … that’s more than a touch).

Here’s a personal statement example:

When I was fifteen years old I broke up with my mother. We could still be friends, I told her, but I needed my space, and she couldn’t give me that.

- Excerpt from "Breaking Up With Mom"

Note how she uses the (funny, but subtle) cliche of “I needed space” and puts it in the context of something that was a pretty big deal for her—cutting her mother off.

Another example:

I’ve desperately attempted to consolidate my opposing opinions of Barbie into a single belief, but I’ve accepted that they’re separate. In one, she has perpetuated physical ideals unrepresentative of how real female bodies are built. Striving to look like Barbie is not only striving for the impossible—the effort is detrimental to women’s psychological and physical health, including my own. In the other, Barbie has inspired me in her breaking of the plastic ceiling. She has dabbled in close to 150 careers, including some I’d love to have: a UNICEF Ambassador, teacher, and business executive. And although it’s not officially listed on her résumé, Barbie served honorably in the War in Afghanistan.

- Excerpt from “Barbie vs. Terrorism and the Patriarchy” in College Essay Essentials and inside our Pay-What-You-Can online course: How to Write a Personal Statement

Again, the humor here is subtle—“plastic ceiling” and the image of Barbie serving in Afghanistan—but it shapes the reader’s impression nicely.

A third example:

Up on stage, under the glowing spotlight, and in front of the glowering judge, I felt as if nothing could get in my way. As would soon be evident, I was absolutely right.

The last kid got out on casserole—I eat casseroles for breakfast.

- Excerpt from “Much Ado About Nothing” on this post on writing about weaker challenges.

Far less subtle, but pretty great—that essay is full of puns and wordplay that demonstrate a strong level of craft (but it took him many revisions to get there).

If you want to try incorporating humor into your writing, great—just be sure to revise several times, as you’ll want to walk a refined line.

3. WITH A LITTLE POETRY

Here’s a personal statement example:

Smeared blood, shredded feathers. Clearly, the bird was dead. But wait, the slight fluctuation of its chest, the slow blinking of its shiny black eyes. No, it was alive.

I had been typing an English essay when I heard my cat's loud meows and the flutter of wings. I had turned slightly at the noise and had found the barely breathing bird in front of me.

The shock came first. Mind racing, heart beating faster, blood draining from my face. I instinctively reached out my hand to hold it, like a long-lost keepsake from my youth. But then I remembered that birds had life, flesh, blood.

Death. Dare I say it out loud? Here, in my own home?

- Excerpt from “Dead Bird”

IMPORTANT: Writing poetically is extremely difficult to do—like walking a high-wire—and, if done poorly, this can fail spectacularly. I’d only recommend this if 1) you have lots of time before your essay is due, 2) you consider yourself a moderately-good-to-great writer and, 3) you’re able to write about your challenges with distance and objectivity (i.e., you have mostly or completely come through the challenge(s) you’re describing). If you’re short on time, don’t have a lot of experience writing creative non-fiction, or are still very much “in it,” I’d recommend not choosing this method.

Straightforward and direct … and with poetry?

In case it seems like I’m contradicting myself by saying that you can be simple and straightforward and be poetic: I don’t think these are necessarily opposites (certainly not here, at least). The kind of poetic language I’m talking about here isn’t flowery or fanciful. Some of my favorite poems are actually pretty simple. But they’re still beautiful.

If you're unsure/insecure about adding humor or poetry, totally understandable, and I'd recommend experimenting with the straightforward method. It'll get you started. And, who knows, maybe some humor and poetry will emerge.

For example, here’s the opening to the “Easter" essay from above.

It was Easter and we should’ve been celebrating with our family, but my father had locked us in the house. If he wasn’t going out, neither were my mother and I.

My mother came to the U.S. from Mexico to study English. She’d been an exceptional student and had a bright future ahead of her. But she fell in love and eloped with the man that eventually became my father. He loved her in an unhealthy way, and was both physically and verbally abusive. My mother lacked the courage to start over so she stayed with him and slowly let go of her dreams and aspirations. But she wouldn’t allow for the same to happen to me.

To my mind, there’s a beauty in how straightforward the language here is. It’s almost poetic in effect.

How to know if your challenges essay is doing its job

The best personal statements often share a lot of the same qualities even when they’re about drastically different topics.

Here are a few qualities I believe make for an outstanding personal statement

You can identify the applicant’s core values.

In a great personal statement, we should be able to get a sense of what fulfills, motivates, or excites the author. These can be things like humor, beauty, community, and autonomy, just to name a few. So when you read back through your essay, you should be able to detect at least 4-5 different values throughout.

When you look for these values, also consider whether or not they’re varied or similar. For instance, values like hard work, determination, and perseverance … are basically the same thing. Whereas more varied values like resourcefulness, healthy boundaries, and diversity can showcase different qualities and offer a more nuanced sense of who you are.It’s vulnerable.

I love when, after reading an essay, I feel closer to the writer. The best essays I’ve seen are the ones where the authors have let their guard down some. Don’t be afraid to be honest about things that scare, challenge, or bother you. The personal statement is a great space for you to open up about those aspects of yourself.

As you’re writing, ask yourself: Does the essay sound like it’s mostly analytical, or like it’s coming from a deeper, more vulnerable place? Remember, this essay is a place for emotional vulnerability. After reading it, the admission officer should (hopefully) feel like they have a better sense of who you are.It shows insight and growth.

Your personal statement should ideally have at least 3-5 “so what” moments, points at which you draw insights or reflections from your experiences that speak to your values or sense of purpose. Sometimes, “so what” moments are subtle. Other times, they’re more explicit. Either way, the more illuminating, the better. They shouldn’t come out of nowhere, but they also shouldn’t be predictable. You want your reader to see your mind in action and take that journey of self-reflection with you.It demonstrates craft (aka it’s articulate and reads well).

While content is important, craft is what’ll bring the best stories to life. Because of this, it’s important to think of writing as a process—it’s very rare that I’ve seen an outstanding personal statement that didn’t go through at least 5 drafts. Everything you write should be carefully considered. You don’t want your ideas to come off as sloppy or half-baked. Your reader should see the care you put into brainstorming and writing in every sentence. Ask yourself these questions as you write:

Do the ideas in the essay connect in a way that’s logical, but not too obvious (aka boring)?

Can you tell the author spent a lot of time revising the essay over the course of several drafts?

Is it interesting and succinct throughout? If not, where do you lose interest? Where could words be cut, or which part isn’t revealing as much as it could be?

Next steps and final thoughts

I hope that, after working through all of this post, you feel well-equipped to dive into writing about your challenges.

To do so, here’s what you can do:

Step 1: Value Exercise—get a clearer sense of what core values you want to illustrate throughout your application.

Step 2: Work through the Feelings and Needs Exercise.

Step 3: Outline using the bullet points from your Feelings and Needs column, focusing on “Challenges + Effects,” “What I Did,” “What I Learned.”

Step 4: Draft. Then revise. And revise. And keep going.

Start exploring.

For essay writing tips from tons of experts, check out my 35+ Best College Essay Tips from College Application Experts.